Duntov’s Stealth Fighters – Part 2

Two of the Corvettes that established the racing reputation of Chevrolet’s sports car meet for the first time in a special exhibit at Revs Institute, opening April 6th. The Miles Collier Collection’s 1963 Corvette Grand Sport will be displayed opposite the unique 1957 Corvette SS on loan from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum. Both flaunt the sheer exuberance that has made the Corvette a car apart.

by Karl Ludvigsen

Zora Arkus-Duntov stormed into the 1963 model year with his brand-new Sting Ray, updated from stem to stern. “The car had handling superior to the previous model, lower drag than the previous model,” he said. “I thought that this car would not only snap at GT-type Ferraris but also take increases in power, as subsequent development proved. I felt we would be the very top dog, better than Ferrari in this type of competition. The calculation was made without Carroll Shelby!”

Shelby’s Ford-powered Cobras—husky Ford V-8s in light British AC chassis—seized production-car championships that had been Corvette territory. “Lots of us still felt Corvette should be winning races,” Zora said. Others above and below him in Chevrolet shared that opinion. “Since we can’t build special vehicles and since our production vehicle isn’t capable of competing,” thought Duntov, “maybe we should have a limited production of some lightened version.” This, compelling in its logic and simplicity, was the idea behind the Grand Sport Corvette. Making and selling them could be a profitable enterprise.

Zora’s scheme was only feasible because Ed Cole’s successor as head of Chevrolet, starting in 1962, was Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen. As a new man in the division, Knudsen had several things going for him—and he knew it. He was not hamstrung by preconceived ideas about what could and could not be done at Chevrolet. His inspired revival of moribund Pontiac gave his superiors confidence in his ideas.

With a minimum of fanfare within the corporation, in the summer of 1962 Chevrolet engineers started working on the car they came to know best as the “Lightweight”. In much the same manner that the SS was built, a secret “skunk works” was created in a windowless workshop off a back corridor of Chevrolet Engineering. Those who backed the “Lightweight” were audacious enough to believe that it could not only beat other GT cars but could also be capable of taking the overall wins that counted for world-championship points.

Founded on the brand-new all-independent suspension of the 1963 Sting Ray, the GT version was a look-alike of the new coupe built to the lightest possible weight consistent with reliability. One hundred and twenty-five of these Grand Sport Corvettes were to be built and sold to serious racers on a first-come, first-served basis. Duntov and Knudsen were confident that because these cars would be only raced by private teams and owners, not by Chevrolet, they would not contravene GM’s adherence to the industry-wide ban on racing—which, in fact, had been repudiated by both Ford and Chrysler the previous May.

Steering wheel, shifter, basic instrument cluster and windshield wipers were the only standard Corvette parts used in the Grand Sport. Frame members were tubular steel, carrying a fiberglass body made ultra-thin that dropped onto the frame in one piece. Headlamps were fixed behind fairings of Plexiglas, used also for all windows except the windshield. Front suspension was similar in geometry but much lighter while rear half-shafts—acting as part of the suspension—were beefed up to take greater torque. Britain’s Girling supplied vacuum-assisted disc brakes.

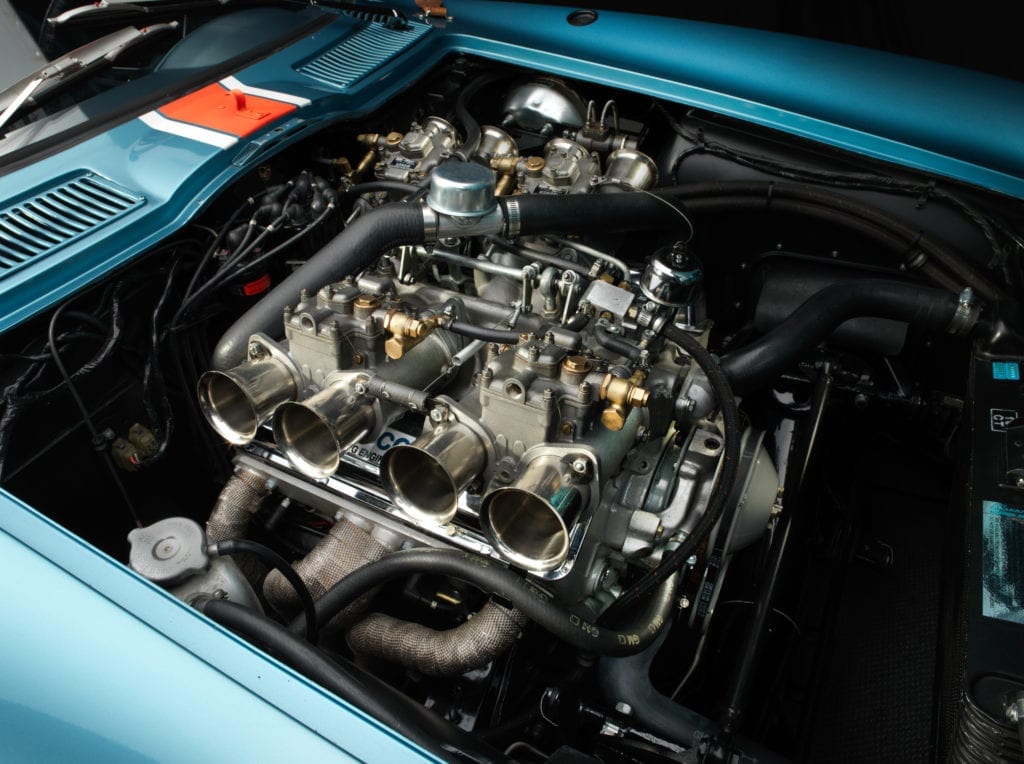

Corvette’s standard V-8 was the basis of the Grand Sport’s engine, although made of aluminum and expanded to 377 cubic inches from the standard 327. Pushrod-operated valves in new aluminum cylinder heads were vee-inclined in hemispherical combustion chambers with dual ignition. The fuel-injected eight produced 532 bhp at 6,400 rpm with 469 pound-feet of torque at 5,600 rpm. No one had yet built a GT or sports-racing car with so much punch.

Parts for the first five cars were made in the skunk works. Bunkie Knudsen authorized the building of 20 more Grand Sports and 40 of the special 16-plug engines. This would be sufficient materiel for the 1963 racing season. The series of 100 additional cars was scheduled for production at the plant of an outside contractor to Chevrolet. Most were to be trimmed as road cars to ensure a broad base of market acceptance. Public launch was scheduled for January 1964 for the production Grand Sport, which was Corvette Model 887. The follow-on, in the wake of racing success, was to be a run of 1,000 cars.

In January of 1963 this promising and attractive program came “to screeching halt” after both external and internal reassertion of GM’s racing ban by chairman Frederic Donner. Wealthy though he was, Bunkie Knudsen was not going to risk his bonus over a few Corvettes. But Duntov had the makings of five cars that could be raced without the 16-valve engines. Though they would have to race against outright ‘modified’ cars, they might make good showings.

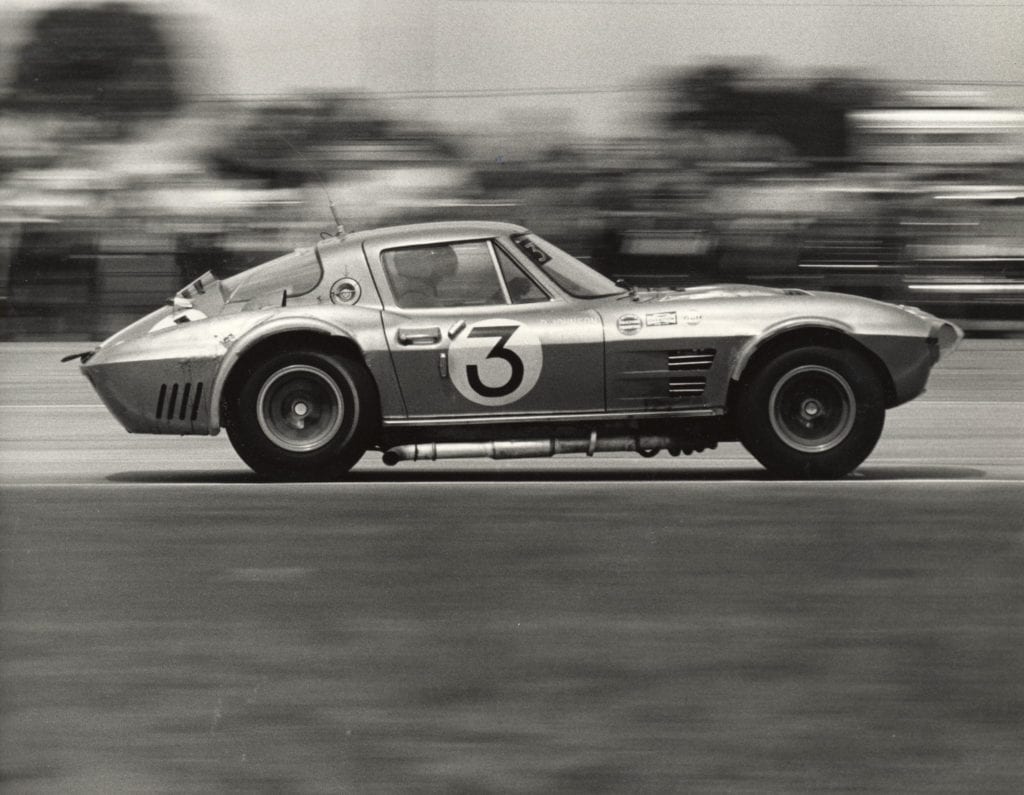

In the hands of dealer Dick Doane and Gulf Oil executive Grady Davis two Grand Sports raced in 1963. Driven by Corvette expert Dick Thompson, the Davis car scored an outright victory at Watkins Glen in August of 1963. Late in the year Chevrolet extensively tested the Grand Sport, making modifications that would not have been allowed in production-car racing such as huge increases in wheel and tire width plus injection improvements that allowed the 377-cubic-inch engines to produce 485 bhp without their special cylinder heads. Moreover two of the five cars were completed as roadsters instead of coupes to reduce their aerodynamic drag.

Under the aegis of John Mecom, Jr, a wealthy and sports-mad Texan, three GS coupes appeared in Nassau, the Bahamas, for international races on the town’s airport in December 1963. Bulging with wide wheelhouses and perforated with scoops and vents, the Mecom-blue-gray Corvettes exuded automotive testosterone.

Although the Grand Sports were still too underdeveloped to compete over long distances, they showed to advantage at Nassau, far outshining the hated Shelby Cobras with 11-second lap-time advantages. “The whole week was a red-letter week for Chevrolet and a black one for Ford,” Zora Duntov wrote to his superiors after his return. “In the last battle of the season in the war between Chevrolet and Ford, the winner and again champion was Chevrolet.”

GS performance gave a much-needed lift to the spirits of Corvette owners and enthusiasts. For 1964 the coupes were sold to private teams, followed in 1966 by release of the two roadsters. In this special exhibit the Collier Collection’s Grand Sport chassis number 004 is presented with the livery of Delmo Johnson’s entry at Sebring in 1964, co-driven by Dave Morgan. This and its sister GS Corvettes are magnificent machines with an awesome air of forbidding malevolence.