A Revolution Now at Revs Institute: The Chrysler Airflow

“There have been few years in automobile history … which have witnessed such drastic and numerous changes in passenger-car design as 1934,” wrote P.M. Heldt, the Engineering Editor of Automotive Industries, a leading trade publication of the time.

The proof of that statement’s accuracy can be summed up in two words: Chrysler Airflow. The word “revolutionary” is overused — often applied to vehicles and technologies that are far from meeting the definition of the word: “causing a complete or dramatic change.” But the 1934 Chrysler Airflow was such a car.

Its arresting exterior design, mechanical configuration, and construction method all served to usher in a new era of automotive design driven by aerodynamics and centered on making the passenger compartment a more accommodating space.

To say the Airflow’s avian-inspired profile was unusual when it was introduced understates its effect by several levels of magnitude. When it had its public introduction at the 1934 New York Auto Show, it wasn’t only the most-talked-about vehicle on the floor, it also set competing auto executives’ teeth on edge. Recognizing that, if successful, the Airflow could make General Motors’ cars seem outdated by comparison, GM started an almost-immediate whispering campaign against the car.

Despite the Airflow’s many notable engineering advances, it was its styling that dominated the discourse initially. The design proved polarizing. In a poll asking auto show visitors to vote for the best- and worst-looking car at the show, the Airflow had the dubious distinction of winning both categories.

Chrysler executive Carl Breer reportedly got the inspiration to build an aerodynamic automobile after seeing a formation of Army airplanes that he had initially mistaken for a flock of migratory birds. The effortlessness of their flight gave him the idea to design a car that could slice through the air in a similarly fluid manner. Of course, there was also a business case for the design: The aerodynamic efficiencies of such a streamliner would make the car substantially faster and more fuel-efficient than its competitors.

In the late 1920s, Breer approached Walter P. Chrysler with his daring idea, and Chrysler gave it the green light, going to the extent of allocating funds for the construction of a state-of-the-art wind tunnel. Chrysler’s only directive to Breer was reportedly to “keep it secret.”

First, Breer’s team set out to investigate the aerodynamic properties of conventional cars. William Earnshaw, one of Chrysler’s engineers working with the top-secret wind tunnel, soon discovered that contemporary automobile designs were so aerodynamically inefficient that they could theoretically achieve higher top speeds while traveling backward than forward.

With the aid of Orville Wright, the team experimented with various shapes until it became clear the “teardrop” shape was the ideal base form for the streamliner. Breer quickly realized that integrating the passenger compartment into the teardrop profile of the car would allow the passenger area to be enlarged significantly without sacrificing aerodynamic efficiency. Accordingly, maximizing passenger compartment space became a top priority for the project.

The first working prototype was a rear-engine, rear-drive design, but this was scrapped due to its unnecessary complexity and awkward proportions. Chrysler adopted a more conventional front-engine, rear-drive design from then on, and it would undergo countless evolutions and wind tunnel tests ahead of its debut as a production car in 1934.

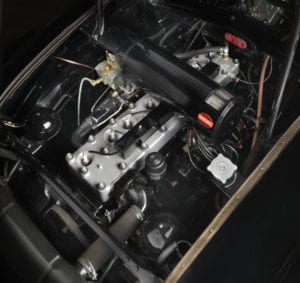

Though at first glance the front-engine, rear-drive configuration of the production Chrysler Airflow looked unremarkable, in its details the layout was a breakthrough. The engine was moved 18 inches forward from the original design over the course of development, eventually sitting directly above the front axle. The car’s wide nose and the space gained by moving the engine forward in the chassis made for a broad and elongated passenger compartment without significant aerodynamic cost. The production Airflow offered a passenger space so expansive that it could easily accommodate three adults side-by-side in both front and back.

Moving the engine forward also changed the angle of the driveline, which enabled designers to lower the passenger compartment by several inches, improving the car’s center of gravity, handling, and ingress/egress. In its final form, the 1934 Airflow was sleeker, longer, and sat lower to the ground than other American cars. By seating passengers within the wheelbase, ride quality and comfort were improved. Chrysler used the term “floating ride” and claimed that the Airflow’s passengers were the first to be truly riding “inside the car.” With automatic overdrive and raked “safety glass” windows, the Airflow marked a radical departure from the norm.

Unlike other cars of the period, the Airflow did not have simple body-on-frame construction. Instead, a unitized cage structure enclosing the passenger compartment was bolted to a cross-membered steel frame, forming a sort of hybrid body-on-frame/unibody, which gave the Airflow around four times the torsional rigidity of its competitors. We take this type of construction for granted today, but it would not be until 1960 — a quarter of a century after the introduction of the Airflow — that any of the American Big Three automakers employed unibody construction at scale. Today, it is by far the most common vehicle construction technique.

While the Airflow pointed to a new, more efficient way to build vehicles, in the moment it presented a production problem. Manufacturing its complex body-frame combination required Chrysler to re-engineer assembly lines. Sadly, Chrysler didn’t take the time it needed to sort out the new manufacturing process properly, inexplicably rushing the car into production a year early.

With the nation in the depths of the Great Depression, some theorize that Walter Chrysler had issued a firm directive that a production-spec show car be prepared in time for the 1934 New York Auto Show, which would be held concurrently with the 1933-34 Chicago World’s Fair. Others allege that Chrysler had discovered the existence of a secret General Motors streamlined prototype in early 1933, and he expedited development of the Airflow in order to beat GM to the show-car stand. (The GM prototype, the Albanita, was actually a technological testbed never intended for production, but it does bear a striking resemblance to the production Airflow.)

After the Airflow was shown at the New York Auto Show, orders from the 1934 equivalent of “early adopters” poured in. But it took months for Chrysler to begin regular production, and the delay caused the public to become skeptical about its credibility. That skepticism was no doubt fueled by the General Motors-inspired underground campaign questioning the car’s safety.

To counter the negative rumors, in August 1934, Chrysler sponsored a series of speed tests to demonstrate the benefits of the Airflow’s aerodynamic design. With Indy 500 driver Harry Hartz at the wheel, a factory-stock Airflow broke 72 separate distance and speed records for production cars. Among these were a flying mile at 95.7 miles per hour, and a 2,000-mile trip at an average speed of 74.7 miles per hour. Chrysler also released a newsreel of an Airflow being pushed off a 110-foot cliff to demonstrate its strength and safety. After it did a somersault on its way to the bottom of the cliff, the Airflow was still able to be driven away on film.

Despite brave attempts to bolster the car’s image, its slow production ramp-up and controversial styling doomed it in the marketplace. Chrysler, which hedged its bets by keeping conventionally styled models in its portfolio, had anticipated sales of 35,000 cars per year for its revolutionary Airflow. Instead, sales peaked in the Airflow’s first year of production at less than 12,000 units. By 1937, with sales down to just over 4,500 units, Chrysler decided to discontinue its landmark car.

Despite being a market failure, the Chrysler Airflow had lingering effects on the world’s automobiles. Soon other manufacturers adopted the lighter-weight steel body construction and better aerodynamics the car pioneered. The spirit of the Airflow is a silent but important part of every car we drive today.

“The Airflow was simply too advanced for a conservative, depression scared public,” Road & Track magazine wrote 20 years after the Airflow’s discontinuation. Right it was, but the Airflow nonetheless left an indelible mark on the automotive industry.

Given its important place in motoring history, Revs Institute recently added a Chrysler Airflow to its collection, marking the first time the Institute, home to the Miles Collier Collections, has directly purchased a vehicle. This new addition is one of the 212 Chrysler Airflow Imperial CV Coupes manufactured in 1934. The model was six inches longer than standard and had more amenities than the regular versions. Often described as the most attractive of the Airflow variants, the Coupe is also rumored to have influenced Ferdinand Porsche’s design of the original Volkswagen Beetle. Sadly, very few examples of the CV Coupes are known to survive, but Revs’ show winning example is now on public display for enthusiasts and historians to admire and study.

For more, watch this 1934 Chrysler-sponsored “newsreel:”