Denise McCluggage

It’s taken a while to sink in. To even half understand we won’t be seeing Denise McCluggage at Pebble Beach this year. Our old friend’s passing at 88 means we had so many great years with her and, yet, still not enough.

It’s gratifying to see so many touching tributes to Denise across the Internet. Telling the great stories about her. How she played the little old lady to avoid a high-dollar speeding ticket. Her racing successes. How she broke through the glass ceiling before we even knew there was one.

But rather than retell Denise stories, we’d like to present some excerpts of her stories. Written for her AutoWeek column, they were gathered for an anthology titled By Brooks Too Broad for Leaping. http://autoweek.com Brooks-Broad-Leaping-Selections-Autoweek/

You’re going to want to buy a copy…

“Why aren’t you driving this?” he said. “This is stupid!” This is ridiculous.”

on riding with Richie Ginther in a Ford GT40

On Jean Behra:

In the 1959-1960 edition of Automobile Year a full-page color portrait of Behra fascinates me. It catches so well the split I remember in the Behra face: His dark brown eyes under his heavy brows could have belonged to two different people. His left eye was always slightly crinkled, as if he knew the punchline to some cosmic joke. That eye twinkled with warmth and life. But the right eye….well, you could get lost in the dark in those depths. And a chill factor had to be reckoned with as well. I sometimes wondered whether people chose to like Behra or to dislike him depending on whether it was his right or the left eye they habitually looked into when talking to him.

On the Rodriguez brothers:

Pedro was 31 on his January birthday in 1971. It looked to be a sterling year ahead. He got his second-ina-row victory at Daytona. Shortly thereafter came three more sports-car racing victories in the Gulf Porsches. At the same time Pedro was establishing himself as a formidable threat for the Formula One championship. He had shown he could drive anything in any weather on any circuit. The respect he had earned was beginning to come.

By July he was lying third in the championship standings. Then at a minor race at the Norisring in Germany, he was driving a Ferrari 512M—leading the race—when the privately-entered car veered out of control.

Some reports said that he went off the road to avoid a slower car. Other witnesses reported seeing the Ferrari’s right-front tire slipping from the rim under braking. Anyway, the ensuing crash was brutal. The 512M left the road, struck a barrier, rebounded across the track, crashed into a barrier and burst into flames. Pedro died of a fractured skull and severe burns. I read the news and

stopped doing what I was doing and thought long about lives that are like shooting stars, as brief as they are bright.

I felt once more Ricardo’s enchanting smile, Pedro’s dark intensity and I was profoundly sad. I went to A.E.Housman. A poet who had written To An Athlete Dying Young would surely have something apt for the young Rodriguez brothers, Ricardo and Pedro.

And he did: “The lads that will die in their glory and never be old.

On riding with in a Ford GT40:

They (Ford) were treating the journalists to a few laps at the wheel of the GT40. You know, the type of articles that results from that: “We test the Champion GT40.” Like that.

When it came my turn the Ford folks, God love their chauvinist souls, opened the passenger’s door for me, not the driver’s side, and asked Richie to give me a ride around the course. I didn’t say a thing. After all, it was their car and they had a right to choose who drove it. Or so I thought then. Perhaps inured to being slighted because I was a woman I didn’t realize until years later how mad at Ford I was. Maybe I was the only woman among the writers, but I was also the only writer there with a competition racing license. (And the only one to have won an international rally as a Ford works driver.)

Nonetheless, it is always a privilege to ride with a really good driver so I hopped in the car. But Richie was furious for me. “Why aren’t you driving this?” he said. “This is stupid! This is ridiculous. He had a very precise way of saying “ridiculous” and the word hissed in the confines of the GT40.

Thank you for that, Richie. Nice ride.

On Steve McQueen:

Steve’s name came up in a group conversation shortly after he had gone to Mexico for the experimental treatments for his cancer and a young reporter among us said: “Boy, that’s the way to make a lot of money right now. If you can get to Steve McQueen you can make a fortune. An exclusive interview.” I said nothing but my mouth opened slightly as I tried to think of a word that described my feelings. Appalled came closest. And I thought, too, that I probably wasn’t much of a journalist.

Appropriately, it was a car radio that delivered the news to me that Steve McQueen was dead. He was 50 years old, the announcer said. Fifty. That had no meaning to me. It was far too young. It was far too old.

I saw then that mid-1950s day in Greenwich Village and a young man with short-cropped hair wearing chino pants and a stark-white T-shirt lounging against his cream-colored TC with its machine-turned dashboard. He squints into the stark-white sun and smiles a quick, notyet-famous smile—one suddenly there, just as suddenly gone. He turns a new white helmet over and over in his hands. I think, too, of those e.e. cummings lines:

And what I want to know is

How do you like your blue-eyed boy, Mr. Death?

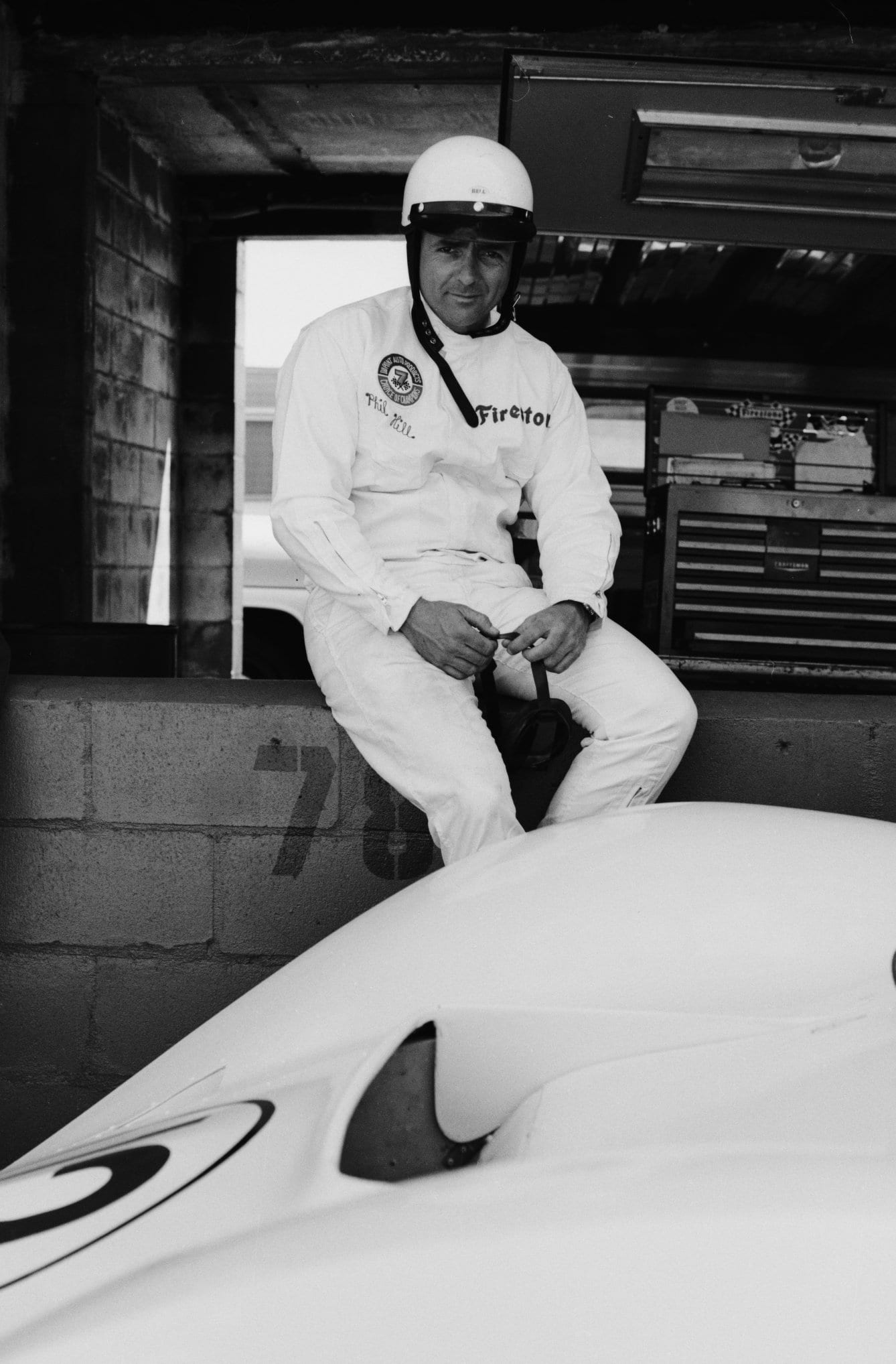

And, of course, Phil Hill, Carroll Shelby and Masten Gregory

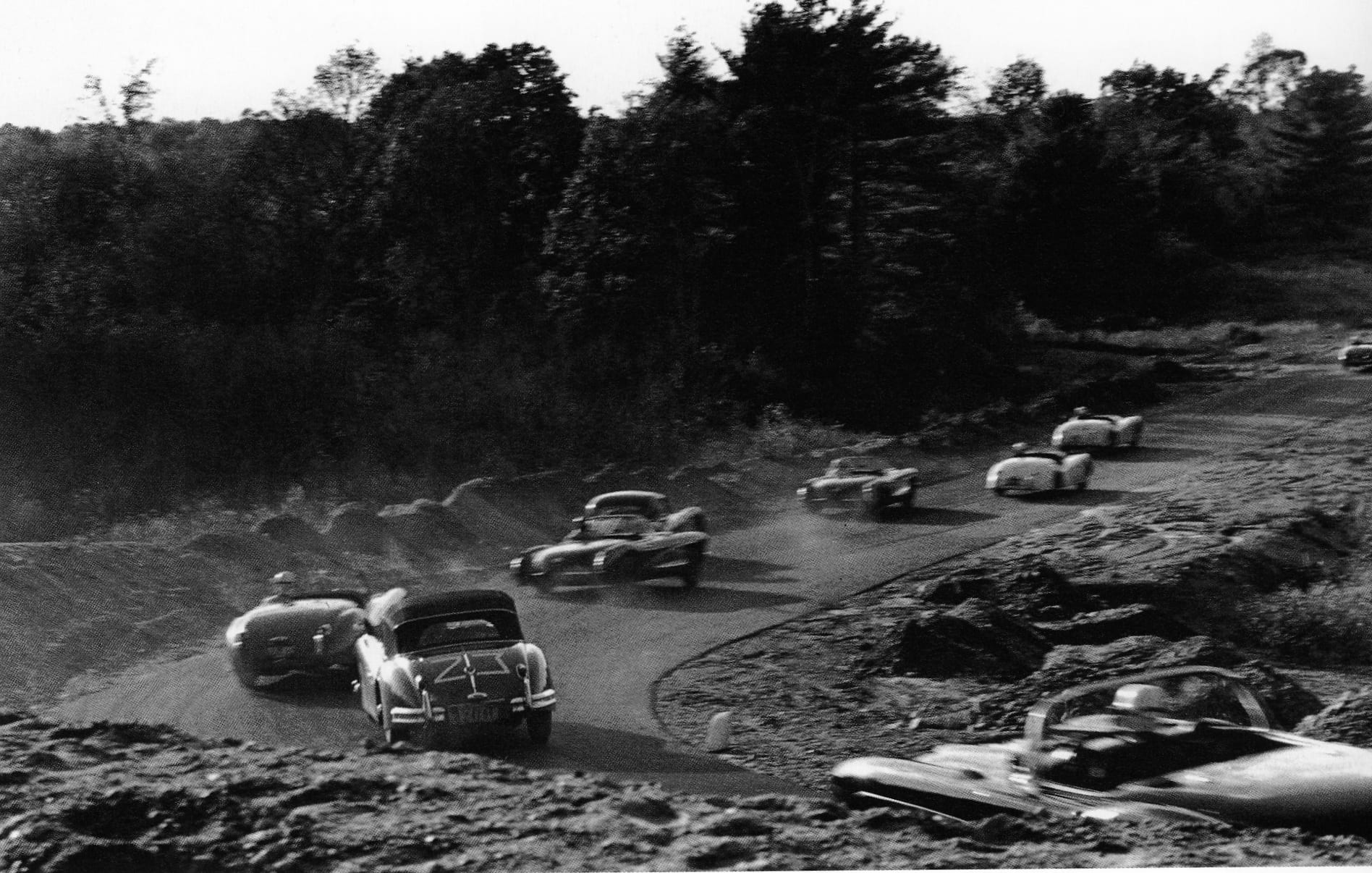

Cuba. Castro was still in the hills though Batista’s days were numbered. There was racing on the Malecon, a wavy stretch of Havana boulevard beside the sea wall. In the pits during practice Phil and Masten and Carroll compared notes. “What are you turning there?” they asked each other. “What did you reach along here?”

Numbers were exchanged—tach readings. They would nod and then each lapsed into silence, inner wheels meshing in thoughtfulness. Then Carroll’s shoulders started shaking in a silent laugh, his face creased. And he said: “I wonder how many lies you and me and Masten have told each other over the years.” They all laughed.

But did the imaginative tach readings that the three recited really qualify as lies? After all, each one knew what his own tach was reading at any particular spot on the course. Each knew whether the other was benefitted in this psyching game by exaggeration or by understatement. So it was really just a matter of practiced extrapolation to come up with the other guy’s actual tach reading. Old friends can’t really lie; they just speak in code.

After one of the practice sessions Phil was in the pits, unscrewing the ear plugs from his ears, going on and on in his usual italics: “You can’t imagine what we are called upon to do out there!” That was his way of saying that the undulations in the course made control of a car at speed a tenuous matter at best.

Masten, Phil went on, was close to buying it. “He doesn’t have a clue!” he said. Phil described with gestures how Masten’s car was behaving on the rough circuit and implied anyone who went that fast under those circumstances was certifiably crazy.

“How do you know what Masten is doing?” I asked. “Well,” Phil said, “I was right behind him all the way.” I simply looked at him until he caught the irony. He shrugged and half smiled.

When I watch the truckers hunched over their cuppa joe and good ole apple pie in some of the lesser stops, counter edges worn from all those elbows, I wonder about what home is to them—a split-level suburban house somewhere with upended tricycles on the lawn? Tow-headed kids slamming out a door with the cry following them: “Just wait’ll Daddy gets home, he’ll settle you!” Or maybe a double-wide on a hill somewhere and a wife who has her own small beauty-shop, does crossword puzzles in ink and bowls every other Thursday.

I watch the truckers and wonder how soon after they get to that home does the home on the road call. Maybe they say it’s the economics that keeps them moving. Maybe it is. And then again maybe some of them just have to get back on that ball of twine. Back to the road.

Just passing through. Just fillin’ up. Just grabbin’ a bite. Just pressin’ on. A schedule to make. The truckers have real-world demands: Pick this up, take that there. But the world of theirs I like most is that other one: the just passing through one.

I could do that.❖

Photos are courtesy of The Tom Burnside Collection which is currently being processed to be placed in our Revs Digital Library which can be viewed here – https://library.revsinstitute.org/digital