From Benz to Waymo (or Way-out), on its 130th birthday the automobile stands on the cusp of multiple revolutions.

Among Detroit’s 2016 Automotive Hall of Fame inductees, with auto-industry hero Alan Mulally and villain (as some would have it) Ralph Nader, was a long-dead and long-forgotten woman, Bertha Benz (1849-1944).

Bitte? Bertha? She drove one of her husband Carl’s Patent-Motorwagens from Mannheim to Pforzheim, Germany in 1888. Her 55-mile trip, long distance in those days, helped establish the viability of the automobile, which Carl had patented in 1886.

So 2016, besides being a momentous year in politics, also was the 130th anniversary of the automobile. And ironically, the act of driving, for which Bertha was honored, is in the crosshairs of technology. CNN declared 2016 to be tipping point for excitement in self-driving cars.

Indeed, despite their increasing refinement, automobiles have remained fundamentally unchanged for their first 130 years. Now, however, they are undergoing several simultaneous revolutions — propulsion, connectivity and autonomy, aka the driverless car. To those three, the car consultants at McKinsey & Co. add “diverse mobility,” meaning car-sharing and ride-hailing services.

They’ll all take the spotlight in the first two weeks of 2017, both at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas and then at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit. The two events are vying for the upper hand in showcasing new automotive technology.

Chrysler is introducing its new electric car in Vegas, not Detroit. But Detroit has snagged John Krafcik, head of Waymo — the new name for Google’s driverless-car subsidiary — to discuss the latest developments in his shop. Also at the Detroit show, Chinese automakers will host a panel discussion titled: “The Race to the Driverless Car.”

With due respects to Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot’s 1769 steam wagon and other attempts to get us out from behind the horse, Benz’s 3-wheel, single-cylinder “vehicle powered by a gas engine” is the granddaddy of all automobiles.

In 13 decades the automobile has gone from novelty to necessity. The car’s U.S. history is often broken into eras. Opinions differ, but here’s a broadly accepted outline.

- The so-called “veteran era.” The origin of the term is unclear, but it lasted from 1886 until the first Model T was produced in 1908.

- The rise of mass production. Henry Ford rode his Model T and his moving assembly line to global dominance through the end of World War I and into the 1920s.

- The rise of mass marketing. GM’s vision of cars as status symbols propelled it past Ford in the 1920s.

- Depression and war. The 30’s and 40’s brought tough times, including the halting of civilian car production for World War II.

- The post-war glory years, lasting until 1973.

- Crisis years. The first oil shock brought government regulation of emissions, safety and fuel economy — along with a new wave of imports from Japan.

Then in 2009 the financial crisis brought near-death experiences and bankruptcy to General Motors and Chrysler. But by 2015 U.S. sales of cars and trucks hit a record 17,470,659 vehicles.

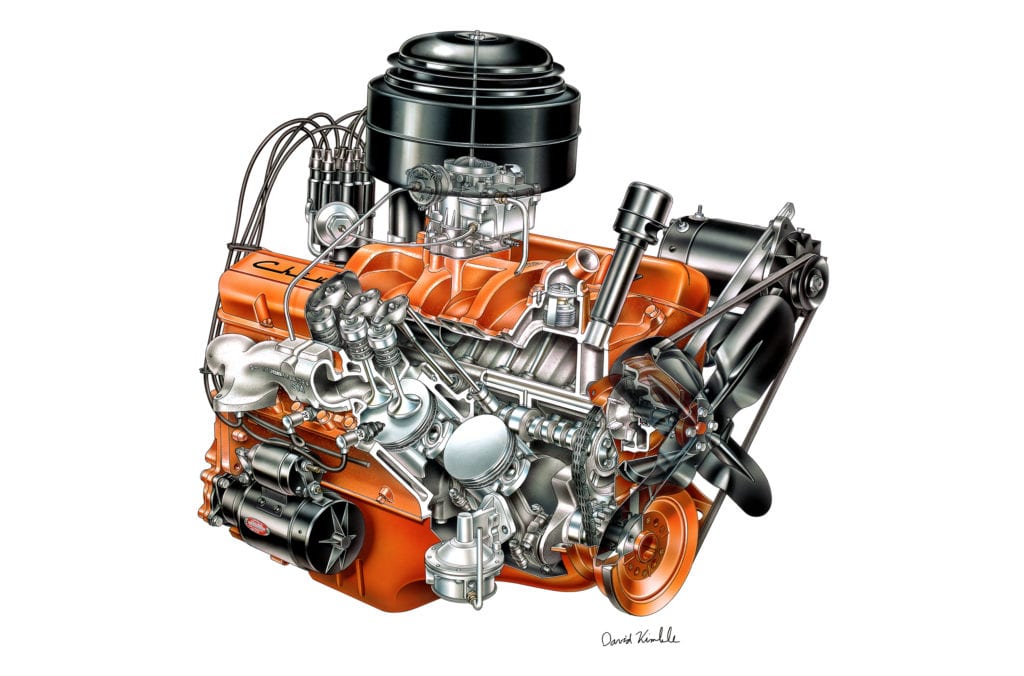

Along the way technology kept evolving. Remember big V-8 powered Cadillacs? As of 2017, only one Caddy, the CTS-V, has a V-8. All others are fitted with turbo fours or sixes. The winner of the 2016 24 Hours of Le Mans was a Porsche 919 Hybrid that matched electric powered with a 2.0-liter turbocharged V-4.

But things are just getting started. On its 130th birthday, the automobile is becoming what would have been H.G. Wellsian science fiction in Bertha Benz’s era. Consider propulsion.

While automotive electric power died away before World War 1, it’s back with a vengeance. Witness a Tesla Model S scooting to 60 mph in 2.6 seconds. More practically, there’s the 238-mile range of the $35,000 electric Chevrolet Bolt (half the price of the Model S).

In Casa Grande, AZ, work begins soon on a factory for another electric carmaker, Lucid, which plans to have its anti-Tesla model, the Air, on-sale in early 2019. Lucid is an example of another new influence in the U.S. car market: Chinese financing.

Better batteries and a growing grid of charging stations mean electric cars are driving off the pages of green-energy publications and onto Main Street.

Google led the pack in developing driverless cars, but now Uber seems to have seized the lead in making them commercially viable. In October the company’s driverless-truck division, Otto, made a beer delivery (50,000 cans of Bud) in Colorado.

It’s a crowded field. Volvo, Tesla, Mercedes-Benz and others have semi-autonomous vehicles already on the road. How long before we have totally autonomous cars? Some experts say five years, others a decade or more.

Technology aside, one issue is the laws governing the development and deployment of self-driving cars. Should the states or the feds set the standards?

What happens when a 20?? Waymo-mobile meets a 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air convertible? Will the old car need an R2D2 for V2V (Vehicle 2 Vehicle) communication with an artificial-intelligence machine?

Now factor in autonomous cars and ride sharing, in which car ownership and pride in your transportation becomes a sometime thing. Could autonomy lead to “auto-anonymity”?

“Millennials not racing for cars,” headlines the Los Angeles Times. So will car brands mean anything in the future? You might enjoy gripping the wheel of your Ford or Jaguar when driving, but if it’s driving and you’re working with your laptop, do you identify with the vehicle?

Automotive guru Bob Lutz commented in Automotive News, “If you get on a city bus or an airplane, do you

care who made it? There won’t be anything left of car brands in 20 years.”

So what happens to the love of the automobile? Will Bertha’s epic drive become as unreal as us considering staring at the backside of a horse for hours?

In 2086, the 200th anniversary of the automobile, will there be an automated car class at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance? Then again, will there be a 2086 Pebble Beach Concours for automobiles?