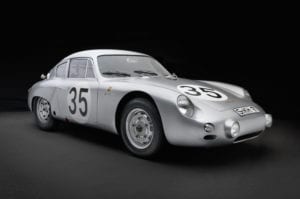

Italian Coachwork and Porsche Performance: The Porsche Abarth Carrera GTL

In the Revs’ Porsche gallery it stands — no, crouches — beside its 356SC cousin, a menacing, silvery projectile with but one mission in life: to vanquish!

Interestingly, this Abarth Carrera GTL and its siblings owed their existence to a weight problem.

In the 356, Porsche had developed a true dual-purpose car, one that could be driven pleasurably to work or to a track where it could race competitively and then home again. Its impact upon the 1950s sports car market reflected public affirmation of that fact.

But as the decade advanced, the Reutter-bodied production 356 grew heavier and less aerodynamic as it added new creature comforts and safety equipment. While the Carrera GT version still ruled its 1600GT class on track, the 1300s — the Alfas, the Lotuses and the Fiats — were closing the gap and challenging the Porsches.

As the 1959 racing season advanced, a dilemma faced Porsche’s corporate leadership. What should they do about this threat?

The 1960 GT Regulations provided hope. Chassis, but not bodies, were subject to homologation. Entrants could substitute lighter, more aerodynamic bodies as long as completed cars weighed at least 95% of their FIA Appendix J homologated weight. Porsche went shopping for someone to clothe their GT racers in more svelte raiment for the following season.

But it soon became obvious that no German coachworks could supply the bodies in time for the 1960 racing season, a fact that led Ferry Porsche to turn to an old friend for help. Austro-Italian racer-cum-entrepreneur Carlo Abarth was well-known in the racing world as an ingenious constructor-modifier-tuner with a wide circle of contacts in the Italian automotive realm.

Abarth and Porsche had worked together on the Cisitalia GP car project in the late 1940s.

Abarth was more than ready to join in the new venture, agreeing to arrange the design and construction of a series of 20 alloy bodies that would provide the advantages Porsche sought. Beginning with the design phase, he commissioned noted body designer/aerodynamicist Franco Scaglione to pen the wind-cheating lines of the new body and veteran coachwork artisan Rocco Motto to do the actual body construction in his small Turin carrozzeria. Porsche transported the chassis to Italy, where they would be mated with their new bodies.

In due course, the prototype car, complete except for engine, arrived in Stuttgart from Turin. As Karl Ludvigsen remarked in his book Porsche: Excellence was Expected, “Here was a stunning alternative to Porsche’s standard shape.”

But though pleasing to the eye, Porsche management was disappointed in the body’s workmanship. There were large and uneven panel gaps. Worse still, taller drivers could not function in the cramped cockpit. Windows and door seals were leaky, body lines restricted application of full-steering lock, and the engine compartment was too small to accept the fan shrouds and oil coolers of the Carrera engines that were to be installed there.

Frantic work ensued, with the driver accommodations and other problems ameliorated by lowering the seat rails and with much hammering and cutting in other areas. Then, when the car was test-driven, the engine overheated due to insufficient air supply. That necessitated the slicing of 38 additional louvers in the rear engine lid. The need for these serious corrections was passed on to the Motto shop for application to the succeeding bodies.

With glitches mostly put right, the advantages of the Italian suit-of-clothing soon became obvious. Dubbed “Abarth Carrera GTL,” (Gran Turismo Leicht) the new car was almost 45 kg (100 lbs.) lighter than its Reutter-bodied counterpart, with a slippery form reducing drag significantly. These reductions provided significant acceleration and top-speed advantages (140-mph capability) over its “civilian” cousin. Retail price was set at DM 25,000 (~ $6,200).

Chassis Number 1001 soon atoned for its difficult birth. A 1960 factory entry in six races that year in Germany, France, Italy and England, it finished first-in-class in all six: Nürburgring 1000km (drivers Herbert Linge and Sepp Greger), Le Mans 24 Hours (Linge and Hans-Joachim Walter), 6-Hours Trophee d’Auvergne (Edgar Barth), Tourist Trophy (Graham Hill), Coppa Inter-Europa (Huschke von Hanstein), and 1000km of Paris (G. Hill and von Hanstein).

The most notable was Le Mans, where 1001 saved Porsche’s honor as the only factory entry to finish in the rain-marred event. Much to Linge and Walter’s discomfort, rainwater poured in through numerous leaks.

The floor, however, allowed little or no drainage, leaving the pilots to sit in puddles during their driving stints, their feet soaked by water surging back and forth during acceleration and braking. Even so, the car made 135 mph on the Mulsanne Straight, with additional power seemingly in reserve.

Other GTLs acquitted themselves favorably in various racing endeavors during the 1960s and beyond.

Following the 1960 racing season, 1001 was sold into private ownership with continued racing by a succession of owners. In 1976 it was sold to Miles Collier and added to the Miles Collier Collections, an aging warrior, well-qualified to rest (or crouch) upon its laurels.