London to Capetown in a Hillman Minx: A Journey Through Space and Time

The car itself no longer exists. Both make and model were discontinued long ago and are now mostly, perhaps mercifully, forgotten.

Many of the countries that it crossed on its epic, record-setting journey no longer exist either. And the same trek today would require an armed escort for much of the route.

But 65 years ago this year a Hillman Minx travelled from London to Capetown in 21 days, 19 hours and 45 minutes, beating the previous record time — set three years earlier, in 1949 — by more than two days. The Minx’s journey was extensively recorded in the Feb. 13, 1952 issue of The Motor, a British car-enthusiast magazine of the day that, like the Minx itself, has passed into history.

Copies of every issue of The Motor — all 85 years, from 1903 to 1988 — are housed in the library at Revs Institute in Naples, Florida. While the Institute’s museum, with 115 classic cars ranging from Duesenbergs to a Trabant, understandably gets most of the attention, the library is a repository of automotive history. Its collection includes more than 20,000 books and 3,200 different automotive periodical titles in four languages: English, French, German and Italian.

Among them: every single issue of Car and Driver, dating from 1961, and The Car, like The Motor a British magazine, in which an author opined In the June 4, 1902 issue that automobiles would solve the urban congestion crisis caused by the horse. (Tailpipe emissions had another definition back then.) The periodicals offer glimpses into automotive history, and trips back in time.

What’s remarkable about the Hillman Minx’s London-to-Capetown journey is that the vehicle, far from being a Land Rover or special-duty truck, was an ordinary family sedan produced by Britain’s now-defunct Rootes Group from 1931 to 1970. The car, which already had 12,000 miles on it, belonged to C.G. Hinchliffe, identified as a “Bradford motor agent.”

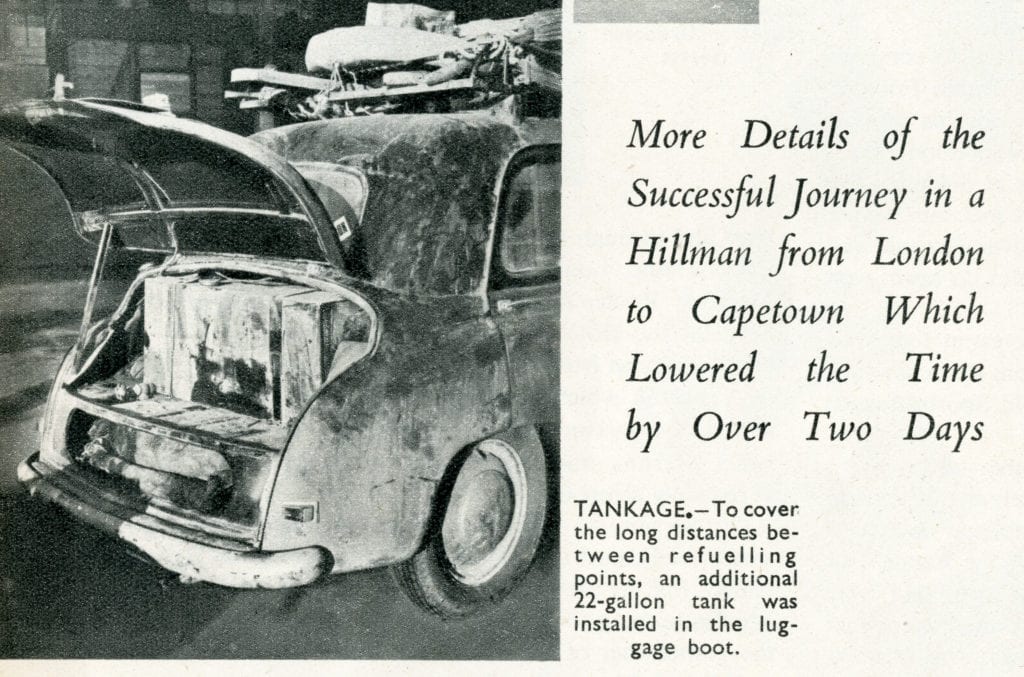

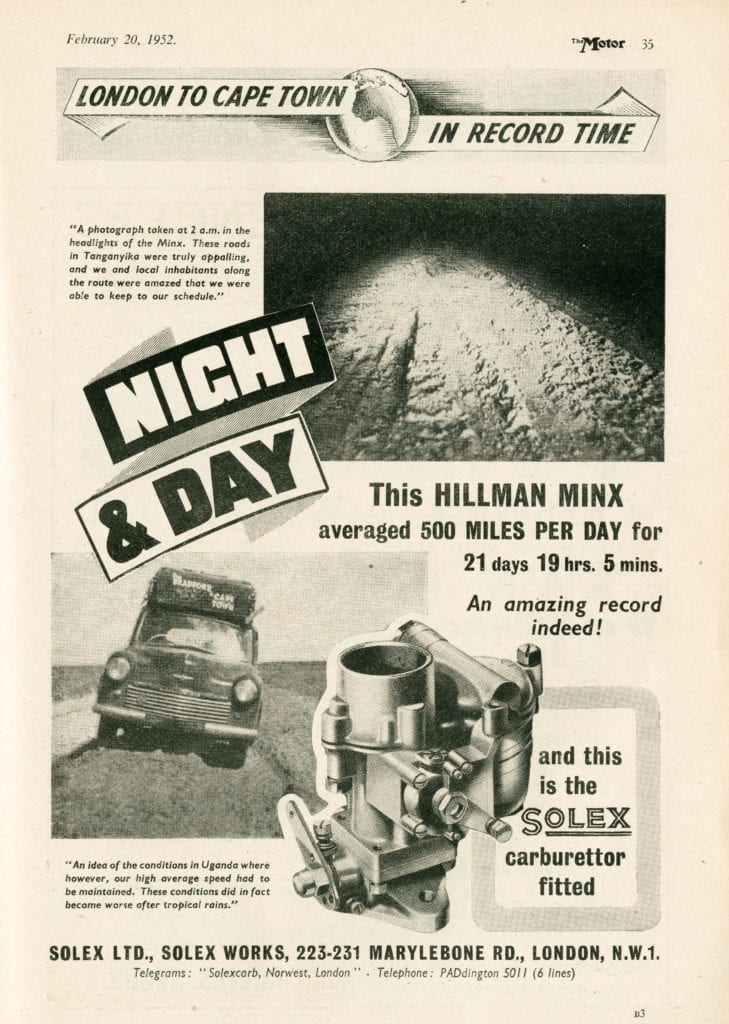

Hinchliffe and his co-driver made just a few modifications to the Minx: a larger gas tank, a water tank, a roof rack and a headrest for the front passenger seat. The 1952 journey appears to have been a marketing gambit. The message, delivered in The Motor with an un-British lack of subtlety, was that if the Minx could make it from London to Capetown, cruising from, say, Norwich to Newcastle should prove no problem.

The Minx started its trek without fanfare on New Year’s Eve 1951 from the Royal Automobile Club on London’s Pall Mall. Shortly after tragedy struck, though not to the car or its two drivers. England’s monarch, King George VI, died at age 56.

The Motor mourned his death in a special editorial that declared: “The life of King George VI (1895 to 1952) spanned almost exactly the birth, growth and overwhelming influence of the petrol age.” The magazine also wished the best for his daughter and successor, Elizabeth II, who still reigns today.

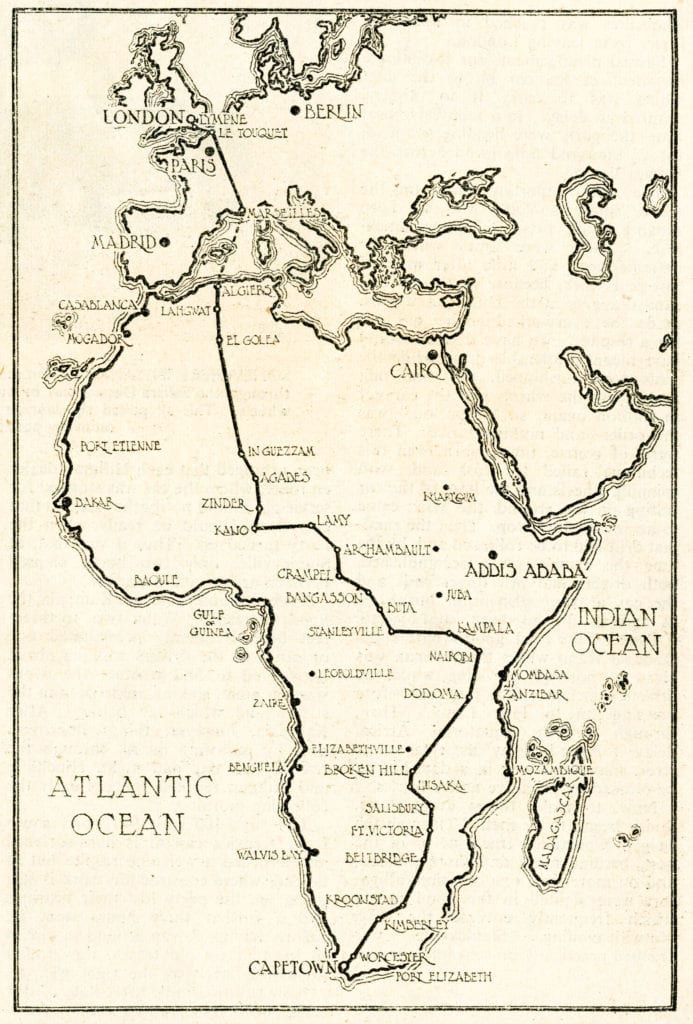

The Minx was loaded on a cargo plane to cross the English Channel, enabling it to make the first leg of its journey, London to Marseilles, less than 24 hours. Then the car crossed the Mediterranean by boat from Marseilles to Algiers. “In a relatively short time, the party were heading south on the 2 ½ thousand-mile grind across the Sahara desert,” The Motor reported.

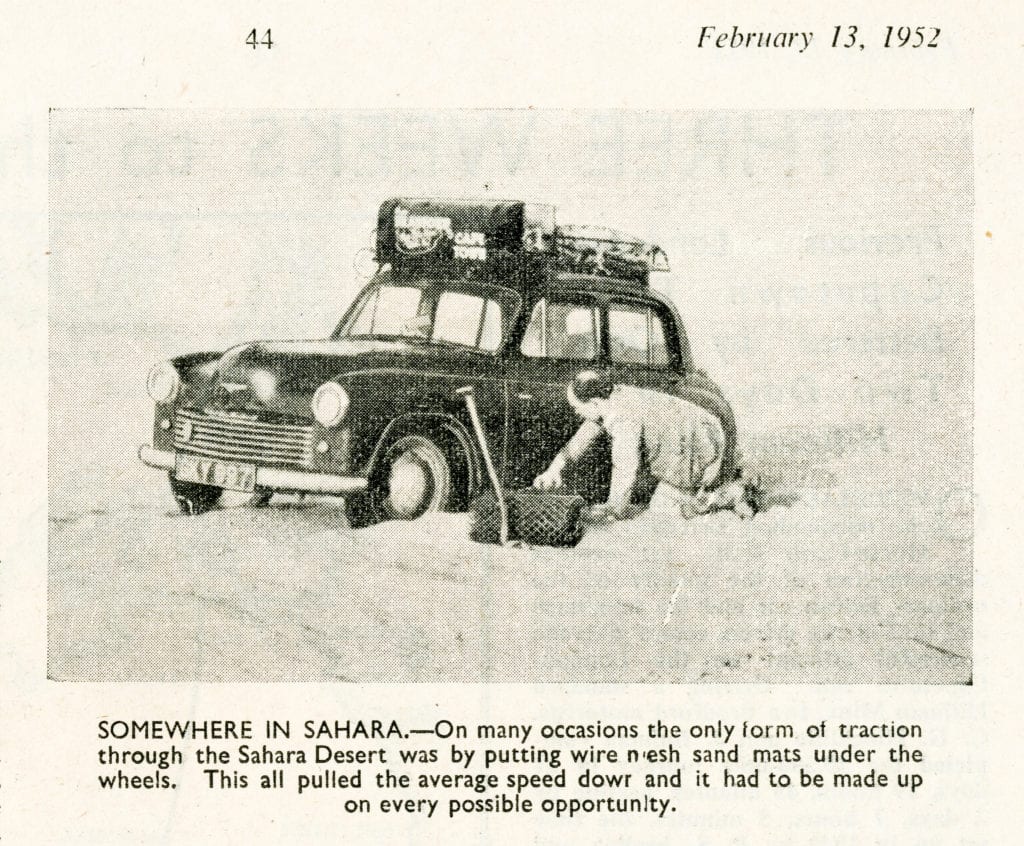

When the Minx inevitably started to slip in loose sand, wire mesh sand mats were slipped under the wheels to provide traction. Before long, “both drivers had raw finger ends and the car a front suspension burnished as though it had been shot-blasted.”

Next came the grasslands and jungles of French Equatorial Africa, which now consists of the countries of Chad, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, the Republic of the Congo and Gabon. Islamist jihadists and other militias operate in some of these places today.

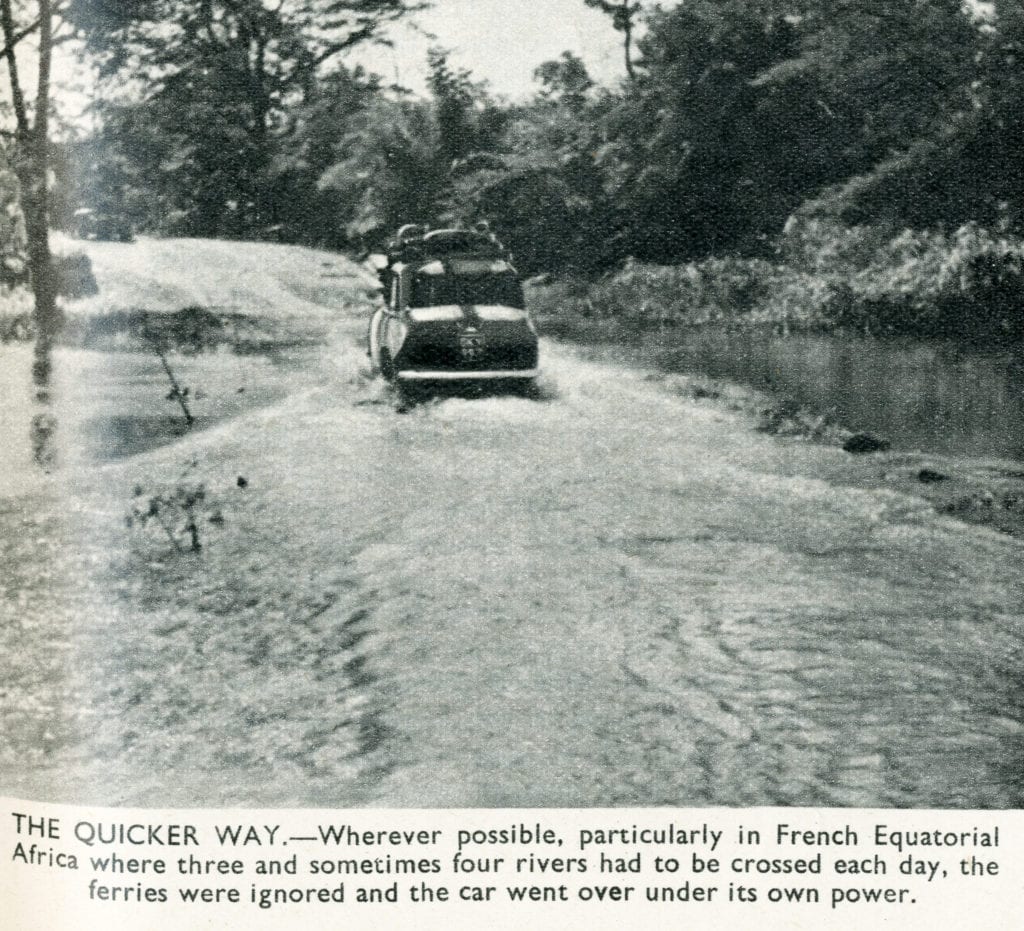

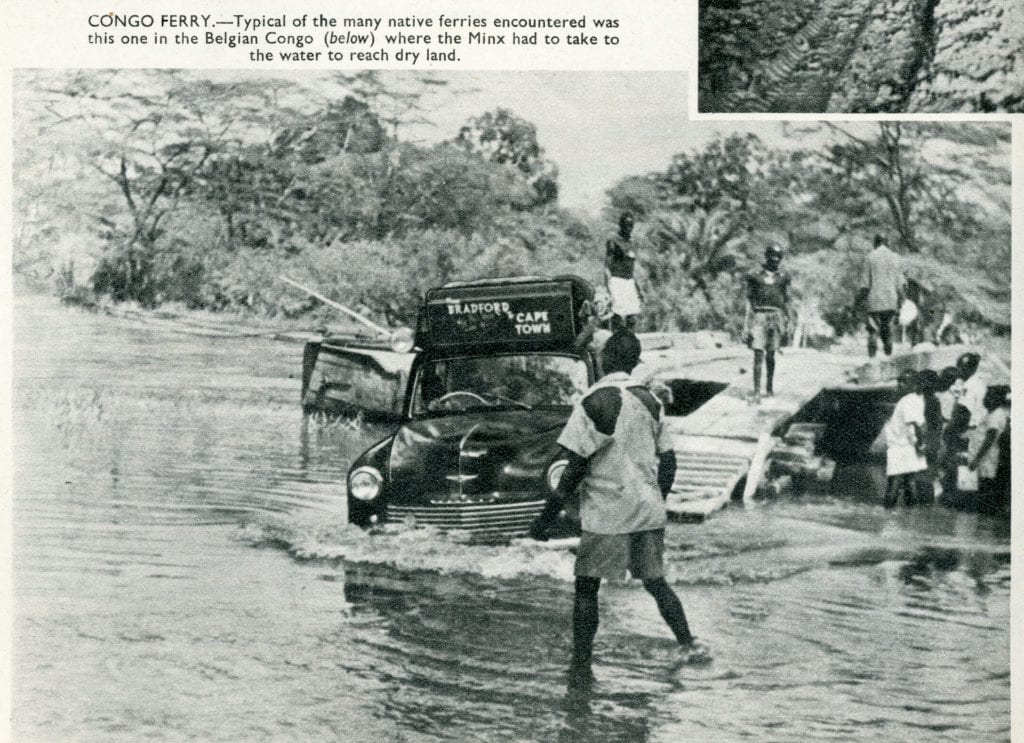

“River after river, sometimes four in a day, had to be crossed by primitive native ferries,” reported The Motor, in language that would be politically incorrect today. “On more than one occasion, alligators were sighted in the flood waters which frequently covered the way.” Reptilian precision wasn’t an issue either; alligators don’t live in Africa, crocodiles do.

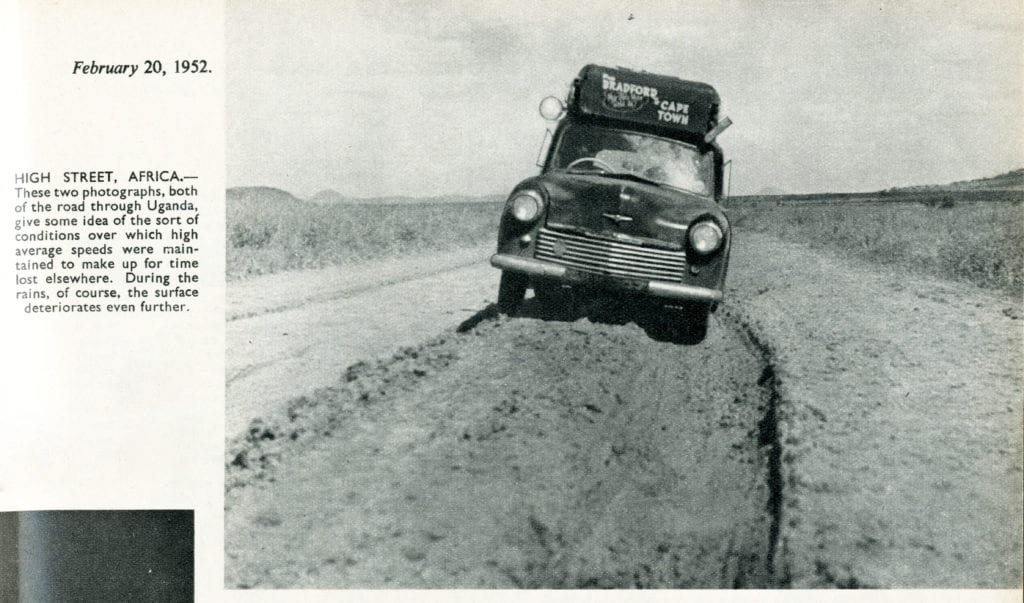

South of Nairobi the Minx and its drivers got lost, driving at night in circles for a while. Then a 170-mile detour to avoid flooded terrain also cost precious time. The quest for speed meant that “both car and passengers suffered a most frightful pounding” on rough roads, the magazine stated. In Kroonstad, South Africa, when the Minx needed a wee-hours service call, a garage owner and mechanic quickly responded, The Motor reported, “in pyjamas and dressing gown!” Well, blimey.

Then came the final 700-mile dash to Capetown, concluding at 4 p.m. local time on Jan. 21, 1952. The car had covered 10,500 miles at an average speed of 20 miles an hour, including three oil changes and only three flat tires.

The Motor followed its initial article of Feb. 13, 1952 with a two-page pictures spread in its Feb. 20 issue. “Let us honor the combination of two men and a car who slipped so quietly out of London to make motoring history,” the magazine declared.

That issue carried dozens of advertisements from companies who made the Minx’s components: axle shafts, steering gears, bushings, etc. The Rootes Group also ran a full-page ad. Much has changed since 1952, but automotive marketing remains pretty much the same.